-

Learn more about...

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Personality: TAI

- Temperament

- Ability

- Interests

- Recent Blog Posts

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® (MBTI®)

- Creativity

- Parsimony in Personality

- Code Sharing: scienceCareers

- Presidential Candidacy and Personality

- Eysenck Personality Questionnaire® (EPQ)

- The HEXACO Model

- The RIASEC Model

- The CHC Model

- The NEO-PI-R

- see more...

Some people are surprised to learn that personality psychology is an active field of scientific research and that this research is regularly applied in marketing, industrial/organizational, clinical and educational contexts (to name a few). It's not a large field, but it is surprisingly diverse and dynamic. Beyond the basic theoretical work, personality and differential psychologists have pioneered several sophisticated statistical techniques and employ a broad variety of data collection methods. None of those topics are addressed here because this site is designed to provide only a basic introduction to the science of personality and the ways that it relates to personality testing. But, it's important to recognize that many of the nooks and crannies in personality research are highly quantitative and technical, even though the field has gained a reputation among the general public for being highly theoretical. If you're looking for more advanced readings, try the Personality Project, which provides references to the work of many former and current scholars on the subject.

Many people have an intuitive sense for personality without ever having taken a personality test. This likely stems from the fact that we're all sensitive to differences among the people around us. In fact, it's hard not to be -- individuals differ on just about every identifiable characteristic and, whether we know it or not, we tend to be quite good at spotting these differences. For better or worse, this skill often leads to the grouping of individual differences into broader categories for the sake of convenience. This short-hand saves us the difficulty (and embarrassment) of having to describe all of the singular qualities that might be needed to describe an individual. Personality scientists are mainly interested in individual differences in psychology (differences in the ways that people typically think, feel, and act), but it's useful to start by thinking about individual differences in physical characteristics because they're familiar to everyone. For example, it's obvious that no two people look alike and, though it's not polite to talk about these differences, we have the tools (language) to describe them in tremendous detail. When we do describe the way someone looks however, it's much more common to use general terms ("attractive") rather than get into all the physical features that contribute to their appearance (height, weight, skin color, eye color, hair length and color and texture, etc., etc.). Of course, this short-hand also introduces some uncertainty. For one thing, more general terms are usually less well-defined -- it depends somewhat on the context or "situation" (this same consideration relates to personality as well). If a very short person describes someone else as tall, does that mean they're only average height? A even more subtle problem stems from the fact that many individual differences can contribute to an evaluation made in general terms. Consider attractiveness. There are many different

Anyway, it turns out that the relationship between individual differences and personality is fundamentally important. They're not synonymous, but individual differences are, to some extent, the fundamental units of personality. Without them, personality would not exist. And the question of how to organize the psychological individual differences has been primary challenge facing personality psychologists over the last 100-125 years. To address this question, personality researchers embraced a profoundly important hypothesis that was developed near the end of the 19th century by Sir Francis Galton. The so-called Lexical Hypothesis states that all of the important features of personality should be codified in language. Most of the research done on personality over the last several decades has used this hypothesis in one form or another to develop lexical-based organizational frameworks (these are sometimes referred to as taxonomies of personality traits). In essence, researchers have been trying to figure out the best way to organize the adjectives we use to describe one another -- a task that is considerably more difficult than it sounds.

The lexical hypothesis will never be truly "proven" (in fact, it's not really a proper hypothesis), and many researchers are reluctant to concede that all the important features of personality can be distilled down to a list of adjectives. Several other useful and intriguing conceptualizations have been proposed and several of these are now the focus of their own lines of research. A short list of the bigger ideas might include: acknowledgement of the fact that personality is a function of perspective (the observed reputation vs. the internal identity), the emerging use of narrative methodologies to evaluate the development of identity, and the recognition of various "characteristic adaptations" that result from the interface between an individual's innate traits/dispositions and the idiosyncratic features of their environment. These ideas are not mutually exclusive, nor are they necessary

One of the goals for the SAPA Project is to evaluate some of these models across very large and diverse populations. Based on the data collected so far, it appears that there are at least two domains of individual differences that are psychologically-oriented but not well-described by the lexical models. These are the Abilities and Interests domains which are described below, right after we discuss Temperament.

The Temperament domain is what most people think of as personality. It's also very well-described by models based on the lexical hypothesis (see above). The most broadly accepted framework of Temperament is known as the Big Five model, which basically claims that there are five broad, dimensional factors of personality: Extraversion, Emotional Stability, Conscientiousness, Agreeableness and Intellect. These factors are sometimes defined a bit differently by various researchers (you may hear the labels "Neuroticism" and "Openness" instead of Emotional Stability and Intellect, respectively). The description of the factors as dimensional is very important. This means that these are not "yes or no" factors but rather that all individuals are described by each factor to some extent. In other words, the dimensions describe the variability among people. You can be a little bit or a lot more (or less) Extraverted than average, but it wouldn't be accurate to say that you have no Extraversion.

While the validity of the Big Five model has generally held up over the last 20+ years of testing, more recent evidence suggests that it performs less well across cultures. Part of the problem seems to be that five is not the "right" number of factors for many cultures (six and sometimes seven is more appropriate). Another issue stems from the fact that the organization of factors themselves seems to vary subtly from one culture to the next. So, most researchers agree that, while the Big Five represents a monumental accomplishment, there are still several important details to be worked out. Feedback on the SAPA Project is based on six factors (the five listed above plus an additional factor for "Honesty and Humility"). Purists might argue that the addition of a sixth factor changes the make-up of the other five factors, but... that's an advanced topic for another time.

There is a

The model of Temperament currently being used for feedback on the SAPA Project is based on empirical analyses of the items in many of the most popular personality tests. For four years, we administered a mixture of items from more than 150 different personality scales -- several dozen personality tests -- and then used extensive statistical procedures to identify a taxonomy of personality traits that organizes individual differences in temperament at two levels. The highest level matches the familiar traits of the Big Five. The lower level captures 27 different traits. After you have completed the survey, you will receive scores and written feedback on all of these traits as well as an indication of how your scores compare to other individuals who have already taken the test. For more information about these procedures, see here.

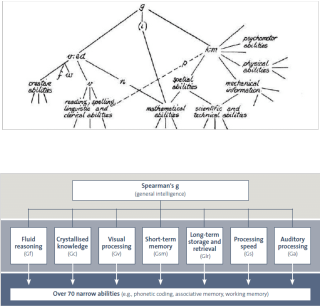

In general, the work of personality psychologists in the United States has not addressed individual differences in cognitive ability over the last few decades. There are some excellent exceptions to this claim and, it should be noted, that researchers in Europe and elsewhere tend to consider the influence of cognitive ability much more commonly than research groups in the United States. There's no denying that it's a controversial topic, one that is complicated by strong associations between scores on IQ tests, education, and socioeconomic status -- all of which are highly predictive for many important life outcomes. Despite the controversy, many researchers feel that the need to account for cognitive ability in personality assessment is an important step towards disentangling these associations.

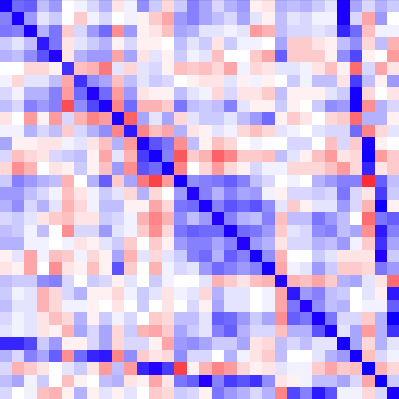

Given this problematic dynamic, one of the priorities for the SAPA Project is to evaluate the relationships between the domains of Temperament and Ability. This will allow researchers to proceed on an empirical basis. If, for example, cognitive ability assessment failed to provide useful information about individuals beyond the assessment of Temperament, then this might support the argument that cognitive ability research is relatively less important (spoiler: this is not panning out -- cognitive abilities do seem to be distinct from Temperament, unless one uses an unusually broad definition for Openness).

It's also worth noting that cognitive ability research -- especially, intelligence assessment -- was one of the first (and among the largest) contributions of psychological science. Despite this, many questions persist about its structure, in part because cognitive abilities are difficult to assess in large samples. Individualized assessment, though more precise, tends to be very time-consuming (no one wants to be responsible for giving out unreliable reports about someone's intelligence). One of the goals for the SAPA Project is the development of measures which place less emphasis on individual precision but are still valid across broad populations. The cognitive ability items that are included in the SAPA Project personality test are a subset of those that have been made publicly available in the International Cognitive Ability Resource.

Interests are an important source of individual differences in terms of day-to-day activities. They are arguably a function of both Temperament and Ability in the sense that what we want to do is partly driven by how we typically behave (Temperament) and what we are capable of doing (Ability). Interests would fall squarely among the "characteristic adaptations" described earlier as few people would argue that they are innate.

Research on the structure of interests has been an important contribution from the field of vocational psychology, though the majority of this work has focused on the occupational correlates of